History

The Original MLC Proposal

Developed in 1967 by Emil and Helen Abramovic, Abe Bialostosky, and the team they assembled

THE MLC ARCHIVE holds at least one version of the founders' original proposal for creation of an alternative school in Portland. The document is startling, for while every story written since—basically all of this website—shows MLC in retrospect, only the proposal shows MLC prospectively, as a vision.

The proposal was readied for and, after some iteration, presented to the Portland Public School System in 1967 by Emil Abramovic, Helen Abramovic, and Abe Bialostosky. The trio, with their combined decades of experience with kids, classrooms, administrators, educational politics and anti-establishment perspectives, had determined what their school would have to look like to succeed.

As MLC parent and organizer Alisa Welch put it in her excellent short history of MLC's origins, "... a one-size-fits-all philosophy of curriculum that left many children behind, uninterested, or disenfranchised was no longer acceptable."

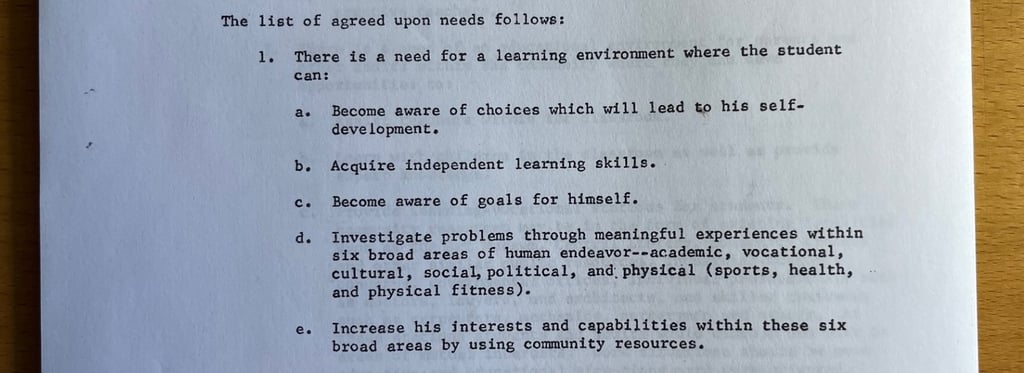

The drafters envisioned a school incorporating a very intentional mix of innovations: representative demographics, democratic decision making, student self-direction, continual exploration by teachers, parental participation, and radical community involvement.

The proposal is also remarkable for showing what has to be considered an unlikely effort to make something truly huge happen. Three working educators, none especially prominent, just tired of watching young people grow alienated from tradition-bound education, stepped forth with vision, energy, and conviction. They enlisted support from eighteen prominent educators and community members, providing heft. They proposed taking gigantic risks with public trust and young lives and signed on to make the risk their own—to make it their life's work. It might have failed. It did not.

Any early MLC student will recognize that some things worked out as envisioned, some did not. Once the proposal became reality, a sort of structure was put in place, into which 150 kids and a small passionate cadre of adults were poured, who then went and did things the way they did them!

Emil, for example, in the 2003 video interview he conducted with alumna Paty Baum, expressed his disappointment that the vision he had for MLC's high school students, based in "lofty goals," as the proposal put it, never quite rose to meet his hopes.

Founding principal Amasa Gilman, in his September 1969 report to Portland Public Schools about MLC's first year (which miraculously survived—images also below), delivers a punchline regarding proposed, careful systems of evaluation: "Students in the Center accepted, literally, the idea that they were to determine what they were to do and expected the school to refrain from the imposition of limitations. They did not want to submit to testing ...."

Non-appearance of some proposed innovations is a mystery. MLC was to have bused kids in from Corbett and Clatskanie, Sandy and Sherwood. It was to have had a board of directors—those eighteen original intellectual champions. It was to have relied on "vocational stations" for learning within the community. Instead, it seems, the school grew quickly resistant to too much engineering, its reality much more free-wheeling.

We, 57 years' worth of alumni and teachers, were as citizens of a new country, creating it as we went. In this pataphor, the founders' proposal exists like a constitution. History, proposal, report, and other early documents yet to be mined will inspire a thousand new questions about exactly what and how the brain trust of teachers, adults, and students innovated over the years, adapting the founders' idealistic-slash-realistic 1960s vision, keeping it alive.

A full history of MLC's development and approval, drawing on conversation notes or minutes of the 31 meetings listed in the proposal, has yet to be written. Alisa's history, drawing on the proposal's rich contents, offers a starting point. It captures the hunger for change, civic openness to experimentation, and the founders' enormous aspirations, all of which helped lead to their (our) remarkable success (click above, or here, to view the original proposal).

Just below: thumbnail—key introductory section of the proposal. Further below: Amasa Gilman's September 1969 first-year report to PPS.